AI in Art context

Alice White, Artist and Art Lecturer, Collaborator on AHA!

The 3 pictures in this selection (see below) help to characterize a larger data set (324 pictures in total). The first has an illustrative quality as attractive as a children’s book — if the book in question held a message of warning to future generations. The second shows a quasi-architectural scene, in which every feature and figure is transformed on several metaphorical and literal levels. The third is a portrait: one of the most familiar art forms produced by humankind.

How do these relatively staple subjects of Art fare in the ‘hands’ of Artificial Intelligence? The texts below seek to open up an artistic exploration into the rapidly changing landscape of AI generated images, with a view to asking what kinds of tools we might need to survive and thrive in the new cultural environment they create for us.

A GOOD PERSON

A young boy is giving a gift to the creature next to him. The child is white-skinned and fair-haired. The creature is a huge bug-eyed alien, with a thick greyish-orange carapace made up of interlocking panels. It reaches its’ sharp talons towards the child, jaundiced eyes fixed on the prize. They stand in a rocky, desolate landscape. Toxic fog hangs in the air. This is an AI generated image of what ‘a good person’ is.

No other prompts have been provided: MidJourney has created this whole scene, and the details of each figure, out of only those three words.

The act of giving is almost always good. Perhaps the boy signifies innocence or vulnerability, and the alien symbolises fear of the unknown. But surely the creature possesses good qualities too (even if they seem alien to us)? In truth, an ‘alien’ is a usually cypher, signaling something unfamiliar. By increasing our understanding, we can help to develop our fear-based reactions into more balanced responses.

Why did the AI choose a light-skinned child to represent ‘good’? Given that this prompt inherently implies a position of higher value, the resulting images could expose a limited data set, dangerously skewed towards codified notions of race. Images for the prompts ‘business person’, ‘powerful woman’, ‘scientist’, ‘doctor’ and three out of four pictures for ‘powerful man’ produced a series of all-white figures too. This suggests that AI has the ability to create a comparably monoculture visual world.

If visual culture has the power to reflect and shape our lives, then the way that we are positioned through imagery also has the potential to misrepresent the inherent humanity of all people. In this context, the boy in the picture symbolises a societal imbalance which is as threatening as any monster. The tension between the viewer and image becomes as fraught as the static between the two figures depicted.

Once the initial impact of composition, lighting, colour and pure otherworldly uncanniness fades, the image reveals something deeper. It exemplifies the stand-off between the promise of creative ‘freedom’ offered by AI generated images and the conceivable ethical oblivion ahead of us, as the underlying biases (conscious or otherwise) of a group of computer technicians formulates the echo-chamber of our digital visual culture.

THE COLLECTIVE SPACE OF HUMAN PERSPECTIVES

A vast plaza opens out before us. Its population appears to correspond to hierarchical groupings seen in classical Fine Art painting: the common folk on the lowest tier, sat chatting in groups, their feet placed firmly on the dusty ground. On the second tier are middle-class suits, gazing outward with a sense of achievement. The top tier seems reserved for the (literally) highest thinkers, most of whom seem engaged in complex, solitary tasks. But here is where the familiar structures end.

Several things are wrong with this image. The figures are only partially formed — their faces blurred as if captured in rapid movement, limbs disjointed or disregarded entirely, smoothed away without explanation. Bodies slip carelessly off the second tier platform, suspended awkwardly outside the rules of gravity but not quite within the dreamlike bounds of Surrealism. This is a vision outside human imagination: it is an AI generated image.

The top ‘tier’ is formed by a long steel beam, jutting out over the rim of the sky, creating a startling division between it, and the stratosphere above. Apparently accustomed to this lofty position, the high-society figures do desk work, or dangle their legs over the spectacular sunset below. Above all this, in a realm where one might expect to see deities or cherubs, squid-like forms orbit an egg, floating like satellites in space.

At the very center of the image, where one would normally expect a focal point, is a chaotic seascape at sundown. A boat drifts amongst the debris of half-constructed ships, unrecognizable objects and (inexplicably), some clouds.

The image is reminiscent of Early Renaissance paintings, in which grand arcades with paved stone tiles, arches and columns are angled at extreme diagonals; often towards a single point on the horizon. Requiring a combination of mathematical skill and artistry to produce, the effect (tackled by the likes of Piero della Francesca) creates the illusion that the 3D world— particularly architectural spaces and the people inhabiting them— can exist on the 2D surface of a painting.

In this image however, the rules of linear perspective are followed only up to a point, beyond which all sense and reason is abandoned. The form of each figure, surface, and space is begun and then abruptly discarded. Any coherent concept driving the piece seems to have been cast aside. Our minds struggle to adjust to an image which seems constantly on the point of collapse.

What does this mean for the future of visual culture? AI generated images have the potential to disrupt perspectives, shaking our notions of what can and should be contained, defined, and clarified. They open up a brave new world: where the rules are shifting as quickly as AI can generate them.

PORTRAIT

Traditionally, portrait paintings are loaded with signs, signifiers and visual clues. Although quite evident to the trained eye, these signals are arguably effective for the uninitiated too, due to the fact that so much of our human experience is dependent on the relationship we form with each other. In this case, the ‘other’ is a picture of a human, but many of the cues we respond to are the same as those in a real-life interaction. It’s therefore useful to understand the ‘codes’ of a portrait, especially if the portrait in question has been created by a non-human: an AI.

An artist can use every element of a portrait to highlight (or conceal) the nature of their subject. It’s not just the face which counts: every surrounding feature helps to complete the picture.

Several factors can convey the subject’s societal status, or can be used to project the status which the subject would ideally desire. Quality of clothing, jewellery and shoes (especially rare or refined materials) as well as the amount of skin which is revealed or concealed, are immediate indicators of the subject’s role. Hair on the head and/or face can suggest modes of masculinity and femininity, as well as roughly indicating the age of the sitter. These aspects also showcase the fashions of the era in which the piece was made.

Posture: whether upright and commanding, relaxed and reclining, tense and contorted, or anywhere in between, does a great deal to convey the physical, psychological and emotional state of the subject. There is added expressiveness in the positioning of hands, feet and limbs. The same is true for the openness (or otherwise) of the eyes and mouth, and the arch or slope of the eyebrows. The myriad interactions of these key features can articulate every emotion known to (wo)man.

All these bodily elements suggest the power, potential and even the sexual availability of the subject. Each addition to the wider composition, including books, furniture, objects, animals, and every conceivable element of indoor or outdoor scenery, adds to the narrative effect.

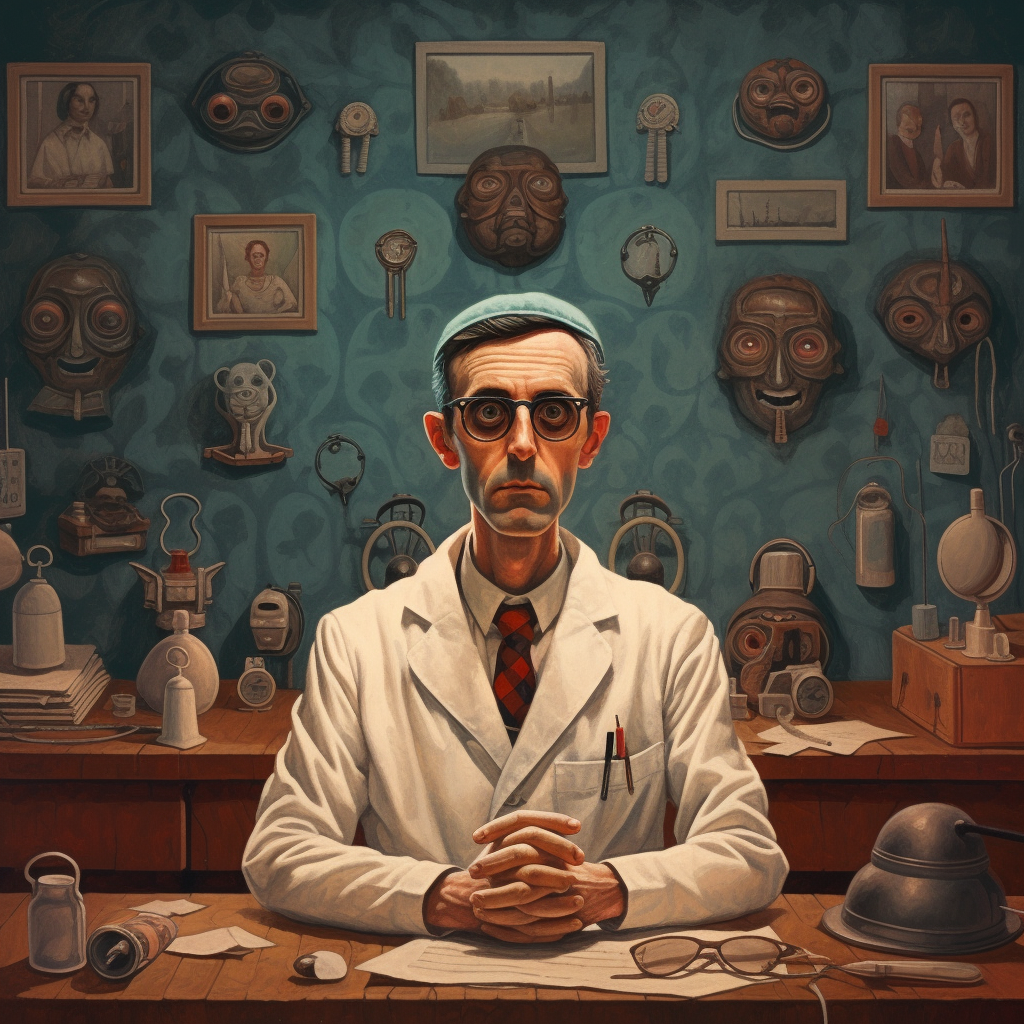

So how does a machine ‘paint’ a human? With the AI image generator MidJourney, the prompt ‘doctor’ produces a set of all male, light-skinned characters. They each wear a white coat, wholly unnecessary outside a laboratory environment, together with a tie or bowtie, which seems old-fashioned. Each doctor is sounded by important-looking papers and books, implying a scholarly mind. In the selected image, the doctor owns not one pair of glasses but two: the second set look decidedly feminine. Surrounding each doctor are the tools of the trade: various vials and vessels which at first glance appear ‘sciencey’ but on closer inspection are only partially recognisable.

AI has an uncanny way of expressing itself through images. The objects in this scene are all like something, but are they actually functional? Without a doctor on hand to verify, one cannot be sure. This is the so-called ‘hallucinatory’ quality reported by researchers, whereby AI produces an image (or output of any kind) which appears plausible, but the accuracy is difficult to determine with absolute certainty. In this case, the doctors’ objects seem realistic, but may have no role in reality as we know it. Once one notices them, the unrealistic objects are everywhere.

On the wall, glaring wooden masks hang alongside commonplace framed pictures. This inclusion seems laughable, until one considers the implications of a doctor of Western medicine surrounded by apparently tribal masks of unknown ethnic origin. It brings to mind notions of the ‘witch-doctor’ or tribal healer, which this Caucasian academic clearly is not. Are these items stolen? The subject and his surroundings are out of place with each other, and out of step with the indicators of trustworthiness and safety which one would rely upon with any professional: most of all a physician. Cultural appropriations seem to have slipped into the image reference bank driving this AI engine.

The doctor sits face-on, at a desk. He clasps his hands, each of which have one too many fingers, and a few extra joints. He wears a surgical cap, but this is no hospital theatre, and his solo act seems purely performative.

This portrait is itself a sign that AI imagery is far from ideal. It could be symbolic of what is to come. The presence, adornments and very creation of this entirely inappropriate doctor causes us to question the role of AI in our contemporary culture. Do AI images confound or confirm our most troubling biases? And what, if anything, is the cure?